Airworthiness is a key aspect of aviation safety and requires constant attention in order to retain the designed-in levels of safety and reliability. Although the worldwide accident rate for transport aircraft has reduced steadily over the years, the fraction of losses due to airworthiness issues has remained the same. The UK CAA study of aircraft accidents for 2002 - 2011 [1] shows the proportion of fatal accidents where aircraft design, engine and systems were a primary causal factor was 10 per cent, with a further three per cent due to maintenance.

In some cases, it is the management of airworthiness that seems to be the issue. In the following examples, it can be seen that standards can fall and errors occur in the presence of unclear roles and responsibilities. Airworthiness regulations already exist to cover design, certification, licensing and maintenance - however, the complex world of contracts and sub-contracts, coupled with human factors - e.g. the "Dirty Dozen" (attributed to Gordon Dupont, Transport Canada) - can still lead to failures.

Managing airworthiness: case studies

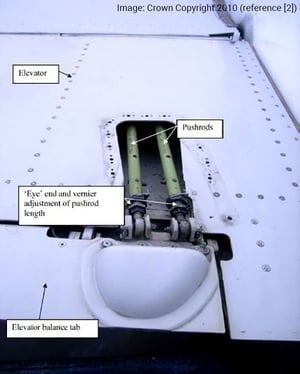

In case 1, a near-accident to a Boeing 737 during a post-maintenance check flight came about due to the mis-rigging of the elevator tab control system [2]. A manual reversion test was carried out by switching off hydraulic systems A and B (a standard test), and at this point the aircraft entered a steep dive. Due to problems in communication during prior maintenance, the elevator trim tab had been adjusted in the wrong sense, leading to a violent pitch down.

In case 1, a near-accident to a Boeing 737 during a post-maintenance check flight came about due to the mis-rigging of the elevator tab control system [2]. A manual reversion test was carried out by switching off hydraulic systems A and B (a standard test), and at this point the aircraft entered a steep dive. Due to problems in communication during prior maintenance, the elevator trim tab had been adjusted in the wrong sense, leading to a violent pitch down.

On the technical side, the AAIB [2] recommended that the manufacturer should amend the Aircraft Maintenance Manual tab adjustment procedure. However, the incident highlights the complex nature of the sub-contracted world of maintenance. Rather than simply categorise this as "maintenance human factors", this incident has all the hallmarks of an organisational or systemic failure. The AAIB recognise this with their recommendation that EASA "review the regulations and guidance in OPS 1, Part M and Part 145 to ensure they adequately address complex, multi-tier, sub-contract maintenance and operational arrangements."

Similar problems in airworthiness management emerge in other areas. In case 2, flight operations of UK Air Training Corps Viking and Vigilant gliders was paused in April 2014 [3]. There was no accident or incident, but the Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation (CAMO) could not be assured of the airworthiness of the aircraft, due to a variety of configuration control and local maintenance issues.

The military duty holders involved have a personal responsibility for airworthiness issues that might compromise risk to life, and therefore took appropriate action - in one way, a good example of risk management. Following a wide-ranging plan to recover airworthiness and a fleet rationalisation, glider operations resumed but the whole Airworthiness Recovery Programme took more than two years.

Finally, case 3 is a further example of how complex contractual and commercial arrangements can adversely affect airworthiness. In July 2016, a Yak-52 (used at ETPS Boscombe Down) suffered a fatal accident while attempting a forced landing following engine failure. The AAIB report [4] and MOD Service Inquiry [5] describe a number of factors, many of which were organisational and show a failure to provide airworthiness assurance. This included the fact that the G-registered (civil) aircraft was operating under a Permit to Fly, which normally prohibits "aerial work".

The cause of the engine failure could not be precisely determined, but it was established that the engine was overdue for overhaul, according to calendar time. There were also a variety of cockpit instruments that were inoperative, which could have made the situation worse.

The cause of the engine failure could not be precisely determined, but it was established that the engine was overdue for overhaul, according to calendar time. There were also a variety of cockpit instruments that were inoperative, which could have made the situation worse.

The importance of human factors

To draw together the above case studies it is useful to adopt the term "airworthiness human factors". Much research has been carried out in the field of maintenance human factors, and it is now a legal requirement to provide training for technical staff. However, maintenance is just one part of the airworthiness picture, albeit a very significant and visible part. Airworthiness also includes the design and certification process (initial airworthiness), plus the management of airworthiness throughout the lifetime of the aircraft (continuing airworthiness).

Future training and education in airworthiness will need to include a wider consideration of the role of human factors. This is not just for the maintenance engineer but also the designer, accountable manager and CAMO staff. Errors occur at organisational as well as local level and extra attention is needed when responsibilities are transferred via contracts and other management interfaces.

References:

1. CAA, CAP 1036 Global Fatal Accident Review 2002 to 2011 (2013).

2. AAIB, AAIB Bulletin: 9/2010, Boeing 737 12 Jan 2009, EW/C2009/01/02 (2010)

3. MOD Duty Holder Advice Notice 86, Viking and Vigilant Type & Continuing Airworthiness Assurance (2014)

4. AAIB, AAIB Bulletin: 11/2017; EW/C2016/07/01

5. MOD Service Inquiry Yak-52 G-YAKB 8 Jul 16 (2017)